The #1 reason private clouds fail is bad storage architecture. Here's how to run stateful services without losing data.

In this post, we move from the philosophy of "cattle" into the high-stakes world of persistent data. We'll explore why stateful services shouldn't be feared if you have the right architecture, and we'll define a production-ready storage stack that prioritizes safety, visibility, and operational simplicity.

We will cover:

- The Storage Mindset: Moving from avoidance to intentional protection.

- The "Sticky" Identity: How Kubernetes StatefulSets keep your data tethered to your compute.

- Replication vs. Backup: Why 3-way replication won't save you from a

DROP TABLE. - Disaster Recovery: Building a "Pilot Light" strategy for site-wide failures.

- Security & Performance: Tuning the stack for production-grade database workloads.

The Tale of Corrupted Data

It was 6:30 PM on a Friday. A developer accidentally ran a database migration in the wrong direction.

The production database was now corrupted.

"We have a backup," someone said confidently.

They checked the backup location. Empty.

"We have replication," someone else offered.

They checked the replica. It had faithfully replicated the corruption within seconds.

The team spent the entire weekend rebuilding the database from transaction logs. They lost 4 hours of data and learned an expensive lesson: replication is not backup.

This post will show you how to build storage architecture that prevents this horror story—or at least makes recovery measured in minutes instead of weekends. We'll cover encryption, backups, replication, and testing strategies that actually work when you need them.

The Storage Mindset

Stateful services scare many infrastructure engineers. The response is often one of two extremes:

- Avoid stateful workloads entirely — Use managed databases, run away from storage, pretend the problem doesn't exist.

- Pick the "enterprise" solution — Deploy Ceph because "that's what big companies use," then spend 6 months debugging it.

Neither approach is healthy.

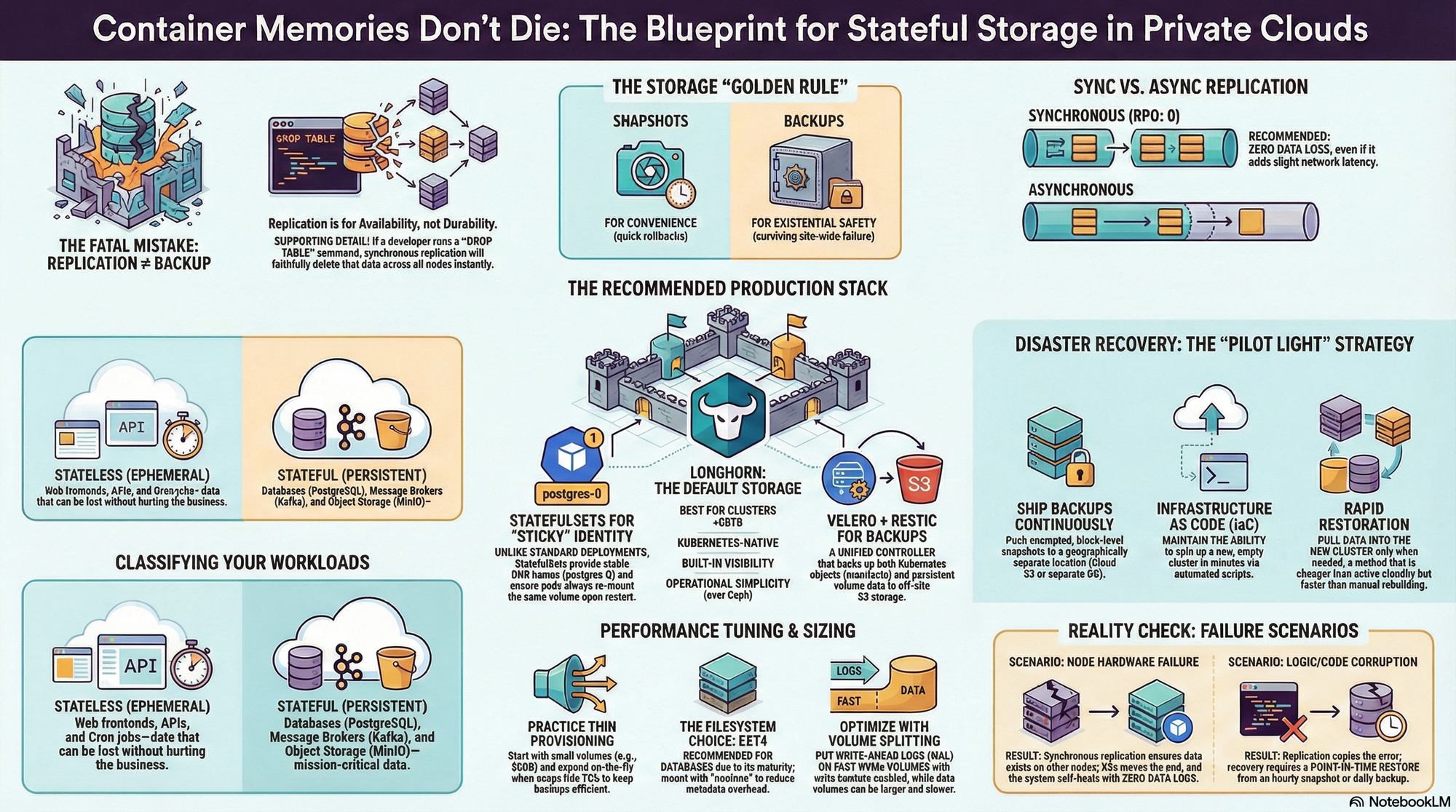

Stateful services are not a dirty word. Databases, message brokers, and object storage are core to any real application. The key is understanding where state belongs and how to protect it.

Stateless vs Stateful: Know the Difference

First, let's classify what actually needs persistent storage:

| Stateless (Ephemeral) | Stateful (Persistent) |

|---|---|

| Web frontends, APIs | Databases (PostgreSQL, MySQL) |

| Message queue consumers | Message brokers (Kafka, RabbitMQ) |

| Cron jobs, workers | Object storage (MinIO, Ceph) |

| Caching layers (Redis) | File storage (NFS, S3) |

The rule of thumb: If losing the data would hurt your business, it's stateful.

The Storage Spectrum

Storage options exist on a spectrum from simple to complex:

| Technology | Scale | Complexity | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longhorn | < 50 TB | Low | SMB, homelab, edge |

| Rook/Ceph | 10 TB - PB | High | Enterprise, multi-PB |

| OpenEBS | < 100 TB | Medium | Cloud-native, multiple engines |

| NFS | < 10 TB | Very Low | Simple file sharing |

Our Choice: Longhorn for <50TB (total cluster capacity)

We're choosing Longhorn as the default storage for most private clouds. Here's why:

- Kubernetes-native: Managed entirely through K8s manifests, not separate Linux commands.

- Built-in Visibility: You can see volume status, replication health, and IOPS metrics in a simple web dashboard.

- Operational Simplicity: No separate cluster to manage, no complex Ceph CRUSH maps to learn.

- Safety Defaults: Every write is replicated to multiple nodes before acknowledging.

Longhorn is block storage, not file storage. Each volume is a replicated block device that your pods mount. This makes it perfect for databases, which expect raw disk-like behavior.

Why Kubernetes Needs "Sticky" Identity

In the world of "cattle," web servers are identical and replaceable. But database servers are unique—they hold specific data.

To handle this, we don't use standard Kubernetes Deployments. We use StatefulSets.

A StatefulSet provides three things databases need:

| Feature | What It Means |

|---|---|

| Stable Identity | postgres-0 is always postgres-0. Its DNS name never changes, even across restarts. |

| Sticky Storage | When Pod postgres-0 dies and respawns, it automatically re-mounts the exact same postgres-data-0 volume. |

| Ordered Scaling | It scales predictably (0 → 1 → 2), ensuring a primary database exists before replicas join. |

This architecture ensures that even though the compute (the pod) is ephemeral and can be destroyed, the identity and data persist.

When to Use Ceph/Rook

Footnote: Ceph (via Rook) is the right choice when you hit 50TB+ of storage or need object storage (S3-compatible API). Ceph can scale to petabytes with hundreds of nodes. But Ceph operations are a full-time job. If you're <50TB and don't have a dedicated storage engineer, start with Longhorn.

When NFS Is Acceptable

Footnote: NFS gets a bad reputation, but it's perfectly fine for small-scale file sharing (<10TB) where you don't need block storage semantics. Use it for shared logs, media storage, or home directories. Don't use it for databases—NFS latency and lock semantics will hurt you.

Volume Sizing: The Elastic Advantage

In traditional infrastructure, you buy a 10TB SAN because you "might" need it in 3 years. In a private cloud, we practice thin provisioning.

The Strategy: Start Small, Grow Fast

Instead of allocating terabytes upfront, we start with minimal volumes (e.g., 50GB). When usage hits 70%, we expand the volume on the fly. This is a one-line change in Kubernetes, and the file system resizes automatically without downtime.

Sizing guidelines for common workloads:

| Database | Initial Size | When to Expand | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| PostgreSQL (small app) | 50 GB | >35 GB used | ~1 GB/month |

| PostgreSQL (production) | 200 GB | >140 GB used | ~5-10 GB/month |

| MySQL | 100 GB | >70 GB used | Variable |

| MinIO (object storage) | 1 TB | >700 GB used | User-dependent |

This approach keeps your backup times short and your underlying disk usage efficient.

Performance Tuning: It's Not Just About Disks

Storage performance (IOPS and Latency) kills applications faster than anything else. Default settings are designed for safety and compatibility, not performance. To run production databases, we need to tune the stack.

1. Filesystem Choice: ext4

We recommend ext4 for general-purpose database workloads. It offers the best balance of tooling maturity, compatibility, and performance. While XFS shines with massive files, ext4 is the reliable workhorse that won't surprise you during a recovery.

2. Reducing Metadata Overhead

Every time you read a file, the system updates its "access time" (atime). For a database reading thousands of pages per second, this is a massive waste of IOPS. We mount volumes with noatime to eliminate this overhead.

3. Write Barriers and Volume Splitting

Modern databases use a Write-Ahead Log (WAL) for safety. A common optimization is to split your database into two volumes:

- WAL Volume: Must be fast (NVMe) and secure. Never disable write barriers here; this is your recovery lifeline.

- Data Volume: Can be larger and slower. You can safely mount this with

barrier=0(disabling filesystem-level flushes) because the database relies on the WAL for crash recovery, not the filesystem. This prevents "double-journaling" overhead.

Snapshots ≠ Backups: Know the Difference

This distinction saves companies.

| Aspect | Volume Snapshot | Off-Site Backup |

|---|---|---|

| What | Point-in-time volume state | Volume data + Metadata |

| Where stored | On the same cluster (local disk) | Off-site (S3, MinIO, NFS) |

| Speed | Instant (seconds) | Slower (minutes to hours) |

| Survives cluster loss | ❌ No | ✅ Yes |

| Best for | Quick rollback before risky operations | Disaster recovery |

The Golden Rule:

- Snapshots are for convenience: "I'm about to upgrade the schema. Let me snapshot so I can revert in 10 seconds if it breaks."

- Backups are for safety: "The data center just flooded. I need to restore our data to a new region."

Use both. Snapshot hourly for fast operational recovery; backup daily for existential safety.

Replication: Sync vs Async

This is a critical decision that most teams get wrong.

| Strategy | Mechanism | RPO (Data Loss) | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous Replication | Writes block until all replicas acknowledge | RPO: 0 (No data loss) | Critical data, DBs |

| Asynchronous Replication | Writes return immediately, replicas catch up | RPO: >0 (Some data loss) | Caches, Logs |

Note: RPO vs. RTO

In disaster recovery, we track two metrics:

- RPO (Recovery Point Objective): "How much data did we lose?" (Sync replication = 0 loss).

- RTO (Recovery Time Objective): "How long are we offline?" (Kubernetes auto-restart = ~1 min downtime).

We prioritize RPO (Data Loss) because you can explain downtime to a customer, but you can't explain why their data is gone forever.

Our Choice: Synchronous Replication

For most private cloud workloads, synchronous replication is the recommended choice.

Why?

- Zero data loss: If a node fails mid-write, the data is guaranteed to exist on another node.

- Automatic failover: When a node dies, the replica takes over immediately without manual intervention.

- Peace of mind: You never have to explain to management why "the last 5 minutes of orders" are missing.

The trade-off is latency—your write speed is limited by your network speed. But in a modern 10Gbps datacenter, this cost is negligible compared to the value of data consistency.

★ Insight

Remember that corrupted database from our opening story? With synchronous replication, the corruption would have been prevented if the node had failed before the bad write completed. But if the bad write succeeded, replication faithfully copies it to all replicas—because that's what replication is supposed to do. This is why we need backups.

Backup vs Disaster Recovery

This is the distinction that saves companies.

| Aspect | Backup | Disaster Recovery |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Restore accidental deletes, corruptions | Recover from site-wide failures |

| Granularity | Per-volume or per-namespace | Entire cluster restoration |

| Frequency | Hourly/Daily | Continuous or On-Demand |

| Storage | Separate S3 bucket | Geographically separate location |

Our Strategy: Velero + Restic

We use Velero as our unified backup controller. It handles two things simultaneously:

- Kubernetes Objects: It backs up your Deployments, Services, and ConfigMaps to S3.

- Persistent Data: It uses Restic to take block-level snapshots of your volumes and push them to S3.

This gives us a single "Restore" button that brings back both the application and its data.

Disaster Recovery: The "Pilot Light"

Backups are just files on a disk. Disaster Recovery is the capability to use them.

We advocate for a Pilot Light strategy:

- Backups are shipped continuously to a secondary location (e.g., cloud object storage).

- Infrastructure as Code allows you to spin up a new, empty cluster in that secondary location in minutes.

- Restoration pulls the data into the new cluster.

This is cheaper than maintaining a fully active standby cluster but faster than rebuilding from scratch manually.

★ Insight

That Friday 6:30 PM disaster from our opening story? With a proper Velero setup, recovery is a single command. The system identifies the backup from 6:00 PM, restores the volume to that state, and restarts the database pod. Total time: ~30 minutes. The team would have been home for dinner.

Security for Stateful Services

Storage without security is just waiting for a data breach. Stateful services have three critical security surfaces:

1. Encryption at Rest

Physical disks get stolen. Hard drives fail and are discarded improperly.

We enable volume-level encryption by default. The storage engine encrypts every block before writing it to the physical disk. The key is managed by Kubernetes. If someone pulls the physical drive out of the server, all they see is noise.

2. Backup Encryption

Your backup bucket is often the least protected part of your infrastructure. If someone gains read access to your S3 bucket, they can download your entire database.

All off-site backups must be encrypted client-side. This means the data is encrypted before it leaves your cluster. Even the cloud provider hosting your backups cannot read them.

3. Access Control (The "No Peeking" Rule)

In a shared cluster, Project A shouldn't be able to mount Project B's database.

We use Kubernetes RBAC and Network Policies to enforce strict isolation. A developer might have permission to view logs, but they should not have permission to delete a PersistentVolumeClaim in production.

Real-World Failure Scenarios

Let's walk through what happens when things break in this architecture.

Scenario 1: Pod Failure

The App Crash

- Database pod crashes.

- Kubernetes detects the failure and schedules a new pod.

- The new pod "claims" the existing volume (thanks to StatefulSet identity).

- Outcome: Database restarts with zero data loss. Downtime is measured in seconds.

Scenario 2: Node Failure

The Hardware Crash

- Entire server motherboard fails.

- Storage engine detects the node is gone.

- Kubernetes moves the work to a healthy node.

- The storage engine attaches the replicated copy of the data (which exists on the healthy node) to the new pod.

- Outcome: System self-heals. No data loss (thanks to synchronous replication).

Scenario 3: Volume Corruption

The Logic Crash

- Bad application code writes garbage data to the DB.

- Replication copies the garbage to all nodes.

- Outcome: We initiate a Point-in-Time Restore from the hourly snapshot or daily backup. We lose data back to the last backup, but the system is recovered.

Storage Anti-Patterns: What Not to Do

Here are the mistakes that cause 80% of storage disasters.

1. "Replication Is My Backup"

Replication provides availability (keeping running if a node dies). Backups provide durability (restoring data if it's deleted). If you run DROP TABLE, replication will faithfully drop that table on all nodes instantly. You need offline backups.

2. Putting WALs on Slow Disks

Databases write to a Write-Ahead Log (WAL) before writing to the main table files. This is a sequential, write-heavy operation. If you share this volume with other random-access workloads (or put it on slow disks), your entire database slows down.

3. Ignoring Volume Health

It is easy to deploy storage and forget it. If a replica fails silently, you might be running on 2 copies instead of 3. Then 1. Then 0. You must monitor your replica count and alert if the cluster is degraded, even if the application is still running.

4. Using NFS for Databases

We see this constantly. "NFS is easy, let's just mount it."

NFS locking semantics are not robust enough for high-throughput databases. You will eventually encounter corruption or locking issues. Use block storage for databases. Use NFS for files.

Summary

You don't need a PhD in storage engineering to run a private cloud. You need a set of opinionated choices that prioritize safety over complexity:

- Use Longhorn for simplicity and built-in replication.

- Use StatefulSets to give your databases a permanent identity.

- Replicate Synchronously to ensure zero data loss on node failure.

- Backup Off-site because no cluster is immune to disaster.

But storage is useless without compute. In the next post, we'll cover high availability design—how to build a 3-node cluster that survives hardware failures.